New York Botanical Garden - 2009

Contents:

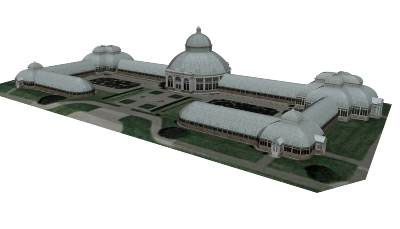

The Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, the nation's largest Victorian glasshouse, is among the grandest indoor spaces in the world. It was opened in 1902 and named a New York City Landmark in 1973. Permanent exhibits include tropical rain forests, deserts, and the world's most comprehensive collection of palm trees under glass. The Conservatory also houses temporary and seasonal flowers shows such as the Orchid Show and the Holiday Train Show. The center of it is the Palm Court with its spectacular 90-foot dome and dramatic reflecting pool surrounded by lush tropical plants.

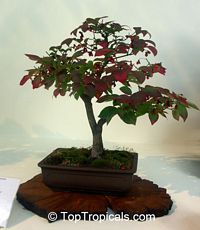

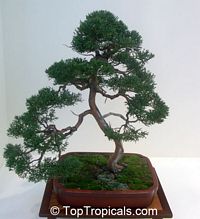

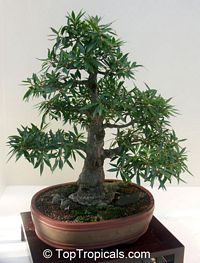

Meaning “plants growing in a tray,” bonsai is the sophisticated and ancient Japanese art of growing dwarf plants in containers. These amazing works of art are displayed in the seasonal galleries of the Haupt Conservatory among simple beds of Japanese plants and chrysanthemums on traditional display tables called tokonoma. The featuring specimens are grown by members of the Yama Ki Bonsai Society.

For the third Fall The New York Botanical

Garden celebrates the ancient

horticultural traditions and brilliant autumn color of chrysanthemums and

Japanese garden plants.

In Japan, the ever changing beauty of the natural world is celebrated and appreciated in many ways. In poetry and art, homes and gardens, foods and festivals, each season is treasured along with its distinctive plants and flowers. Autumn in Japan begins with the annual Chrysanthemum Festival, followed by excursions to view colorful autumn leaves known as momijigari. The foliage of trees and perennials light up the Japanese landscape. Scarlet Japanese maples glow against Japanese black pines and golden bamboos flash against emerald conifers. Throughout the Garden, you can experience the beauty of momijigari as you view the spectacular colors of changing leaves.

Kiku - the art of the Japanese chrysanthemum

A Japanese tradition flowers in the Bronx

The chrysanthemum, kiku in Japanese, is the most celebrated of all the Japanese autumn-flowering plants. Kiku arrived in Japan from China where the flower was admired for its beauty and believed to have medicinal properties that promoted good health and long life. The Japanese Emperor was so smitten with the kiku flower that he adopted it as his personal crest, and it remains the insignia of the imperial family today.

The chrysanthemum, kiku in Japanese, is the most celebrated of all the Japanese autumn-flowering plants. Kiku arrived in Japan from China where the flower was admired for its beauty and believed to have medicinal properties that promoted good health and long life. The Japanese Emperor was so smitten with the kiku flower that he adopted it as his personal crest, and it remains the insignia of the imperial family today.

This is the third Fall season that New York Botanical Garden presents the most extensive display of Kiku cultivated in the imperial style that has ever been seen outside of Japan. The exhibition is a result of the hard work and close collaboration of Yasuhira Iwashita, the kiku master at Shinjuku Gyoen, and Yukie Kurashina, a gardener at the New York Botanical Garden, who spent many months in Japan over the last few years training with Mr. Iwashita and absorbing the traditionally secret art of kiku cultivation. Until World War II, Shinjuku Gyoen was the private garden of the imperial family, and the traditional styles of kiku cultivation were originally designed to celebrate the November 3 birthday of Emperor Meiji, who ruled from 1868 to 1912. The art of kiku cultivation is on the verge of disappearing in Japan. The best gardeners, like Mr. Iwashita, are near retirement, and young people are uninterested in learning the traditional techniques.

Kiku masters have grown and trained the flowers, and they have mastered every detail, from the makeup of the soil to how much humidity the plants want, to how to get them to bloom just at the right time. The exhibition at the Botanical Garden is opening earlier than the traditional Shinjuku Gyoen's exhibition. For that reason, half the plants have been shaded for a certain period each day, to fool them into thinking that it is later in the fall and make them bloom early. After two weeks, they will be switched out for other, later-blooming plants.

Kiku masters have grown and trained the flowers, and they have mastered every detail, from the makeup of the soil to how much humidity the plants want, to how to get them to bloom just at the right time. The exhibition at the Botanical Garden is opening earlier than the traditional Shinjuku Gyoen's exhibition. For that reason, half the plants have been shaded for a certain period each day, to fool them into thinking that it is later in the fall and make them bloom early. After two weeks, they will be switched out for other, later-blooming plants.

Kiku was brought to Japan from China in the 8th Century CE. Over time it has become one of the flowers most evocative of Japanese culture, along with the cherry blossom. In China, this flower has been always one of the "Four Gentlemen" in art. The four plants that are used to depict the unfolding of the seasons are the plum blossom for spring, the orchid for summer, the chrysanthemum for autumn, and the bamboo for winter. As a symbol of longevity and the season of Autumn, the chrysanthemum is commonly depicted in the arts of Japan too, including painting, decorative arts, and literature.

"The Chrysanthemum Spirit" is the story of Sainosuke, a kiku-obsessed man, who meets Saburo, a poor, younger man with an exceptional ability to grow kiku effortlessly. Although unable to control his jealousy, Sainosuke marries Saburo's beautiful sister, Kie. After years of living with envy and frustration over his inability to reach the level of Saburo's talent, Sainosuke accepts his own mediocrity. Soon after, while the threesome is on a spring outing, Saburo, at the peak of contentment after drinking sake, turns into a chrysanthemum seedling. Realizing then that his brother-in-law Saburo and his wife Kie are in fact supernatural beings, Sainosuke feels a new appreciation for them and plants the seedling in his garden. When autumn comes, a single bloom appears, tinged with a drinker's rosy complexion and the subtle fragrance of sake.

For centuries the Japanese had treated their Imperial horticultural art of Kiku like a state secret. A Chinese philosopher once said, "If you would be happy for a lifetime, grow chrysanthemums." Japan has a National Chrysanthemum Day, which is called the Festival of Happiness.

The chrysanthemum is the official flower of Japan and has become a symbol of longevity, power, dignity and nobility. In the Japanese garden the cycle of life from birth to death is reflected in the quiet passage of a year in the Garden. The chrysanthemum is also a metaphor for homosexuality in Japanese poems.

The chrysanthemum is the official flower of Japan and has become a symbol of longevity, power, dignity and nobility. In the Japanese garden the cycle of life from birth to death is reflected in the quiet passage of a year in the Garden. The chrysanthemum is also a metaphor for homosexuality in Japanese poems.

The New York Botanical Gardens offered this exhibition at Haupt Conservatory as the result of five years of a cultural exchange between the Shinjuku Gyoen in Tokyo, where for the past 100 years gardeners have perfected the art of growing and displaying exquisite chrysanthemums for the Emperor's garden. Under the training of Kiku master Yasuhira Iwashita, the techniques and styles developed and displayed at the Shinjuku Gyoen are now presented outside of Japan.

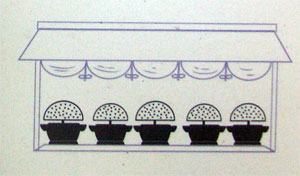

There are four Imperial styles of Kiku which are being displayed. Ozukuri ("thousand bloom"), Ogiku ("single stem"), and Kengai ("cascade"). These plants are all housed and displayed in decorative Japanese garden pavilions known as uwaya. These intricate structures protect and frame the beauty of the kiku displays: they are constructed from bamboo and cedar and then edged with ceremonial drapery.

"Uwaya" - a display place where the plants are housed and protected

Ogiku ("Single Stem") features single stems that can reach upwards of 6 ft tall with one single perfect bloom balanced on top. The six foot high blooms are propagated from one cutting. The cuttings are planted in the spring. By showtime, each plant will consist of a very tall stem with no side shoots and a single blossom at the top. Each chrysanthemum pot is buried horizontally and the plant stem is bent. Flowers are precisely arranged in diagonal lines that decrease in height from the back to the front of the bed, in tri-color color patterns that resemble traditional Japanese reins called tazuna-ue (horse bridle). The combination of lavender, yellow, and white are associated with equine regalia of the Japanese court.

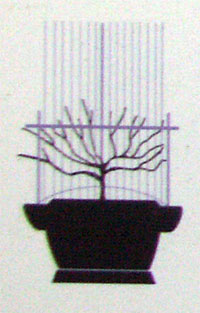

The literal meaning of ozukuri is "to make big," because the final plant must be 8-9 ft across. Ozukuri is a highly complex technique when a single chrysanthemum is trained to produce hundreds of simultaneous blossoms in a massive, dome-shaped array. This style of training Chrysanthemums is the most difficult. It is planted in specially-built wooden containers called sekidai and require a minimum of 11 to 12 months to train - of all kiku, it grows for the longest amount of time. The shoots are planted in mid-November and require the most skill to grow successfully. While the ordered profusion of blossoms appears to be an arrangement of many individual plants, the exquisite Ozukuri configuration is actually coaxed and developed from a single stem, and if you kneel down, you can see the single 1/4 inch thick stem of the entire plant. To create the illusion, the plant is limited to five hardy branches. The gardners turn the lights on in the greenhouse for several hours each night, so that the plants would "think" the long night was actually two short nights, divided by a day, and would concentrate their energy on growth instead of blooming. The shoots from the limbs are then trained to grow straight and blossoms are removed until only the strongest one remains on each secondary stem. The plant's nutrients are thus concentrated in one blossom, creating a quietly dramatic spectacle when all of the flowers are in bloom. In order to get the rows in perfect alignment and ascending smoothly toward the rear, as much as four feet of each stem is buried, sideways in its pot, in the earthen plinth from which they rise. That means they cannot be watered during their two weeks of show. By last week, the plants get attached to their aluminum frames, and the branches are starting to produce buds. In the end, each branch will have one flower, and each plant will have between 200 and 300 blossoms.

Ozukuri step by step:

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6

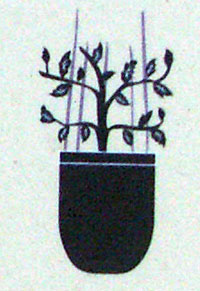

- A small piece of stem is cut from a mature kiku plant. The cutting is planted in its own pot.

- As the plant grows, its tip is pinched off to encourage side branches to grow.

- Unwanted side branches are pinched off te main stem until five strong ones remain: 3 for the front and 2 for the back.

- The plant is repotted into a traditional handmade wooden container - sekidai. Each secondary branch that develops on the existing branches is tied to a vertical stake to grow straight.

- When the plant reaches 6 ft high, its branches are untied onto a complex frame. After flower buds form, all but one are removed from each branch.

- The plants are moved to an uwaya where they will be displayed and protected.

Ozukuri is started in November with a cutting. When it gets to about six inches, it pinchee to allow five branches. Three are set higher and will grow to six feet, in time, to form the front of the ozukuri. The back two form the rear of the dome. Once these branches are long enough to support 11 leaves, the stems are pinched again, and then again, to promote branching.

Pinching stops in July, followed by another technique called disbudding. Chrysanthemums set buds in each leaf joint that, if left, would grow into stems that would bear weak flowers. These tiny buds, literally thousands of them, are removed by hand in summer and early fall. About a month before flowering, the gardeners allow two or three flower buds to develop at the end of stems that by then can reach five to six feet in length. The frame is then designed and constructed, and the stems are manipulated within the supports. The branches are pliant to a degree, but anything but a gentle touch at that stage could mean disaster. You can't rush it. The surplus flower buds, about the size of a pea, are removed based on minute differences in their size. The aim is to get all buds to flower at the same time. The end product may be something highly manipulated and willfully unnatural, but the process represents the essence of gardening.

"Friendship" - 186 flowers |

"Peak of Mt. Takachiho" - 229 flowers |

"Moon Below the Mountain" - 229 flowers |

Another style is known as Kengai, or "Cascade". This technique features small-flowered chrysanthemums that are more typical of the wild varieties. Kengai in their final form are cascades of small blossoms resembling flowers growing down a cliff, or like waterfalls, trained in boat-shaped frameworks with lengths of up to 6-7 ft away from the potted root ball. Kengai require a minimum of 11 months to train. The shoots are planted in mid- to late December of the previous year. They grow straight up for several inches, and then the gardener bends them on a diagonal. Side shoots are pinched off, which makes it grow more side shoots, so that eventually there is a thick forest of small stems, each with its own buds. The stems are eventually tied to a frame, which, ultimately angled downward, produces the cascade effect.

Again, the prolific display of each variety is achieved from a single stem. Hundreds of flowers are trained onto a wire frame which is bent into the display position once the flowers are about to bloom. In its final stage, Kengai recalls an exuberant image of wild flowers on a cliff's surface, thereby mimicking and perhaps surpassing the beauty of the natural world.

Using the exhibition style of the Japanese imperial flower show, the kiku are arranged in temporary bamboo structures known as uwaya. One thus views each style in it's own housing, a display aesthetic that not only protects the flowers from wind and rain, but also encourages the viewer to appreciate each plant as a living and therefore ephemeral work of art. Kiku are not simply natural wonders; their form is the result of careful human manipulation. Yet, rather than imposing an order onto nature, one persuades the plant's natural character into a vision of perfection.